How to Manage 240+ Projects: Long-term Strategies from My 8-Year Journey

Over the past five years, my system has accumulated more than 240 projects—and that doesn't even cover the full eight years I've been using it. These projects span all aspects of my work and personal life, continuously growing and evolving with my needs. So, how can one effectively manage such a large number of projects?

This article will explore that very question: how to manage numerous projects from a long-term perspective within the PTKM framework.

1. Background

The inspiration for this article struck me while I was listening to a podcast in the shower. I realized that many things in our lives—whether concrete or abstract, short-term or long-term—can be managed with a project-based mindset. Even life itself can be seen as a single, lifelong super-project.

In popular productivity methodologies, projects have clear definitions:

GTD (Getting Things Done) defines a project as a collection of tasks, with an emphasis on completion and closure.

The PARA Method categorizes information into four domains: Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives. Here, projects are just one component, coexisting with areas and resources.

While these methods certainly have their merits, my eight years of exploration and practice have led me to an approach tailored for long-term project management. I hope it offers a new perspective on how to manage projects.

2. Project Pages

Within the PTKM (Project, Task, and Knowledge Management) framework, I create dedicated project pages for significant and valuable projects. For example, here is the project page for my Obsidian plugin development:

As you can see, these pages are composed of several distinct elements.

Project Action Notes: These notes contain a series of tasks, similar to a traditional project plan. However, a key difference in the PTKM framework is the sheer volume of tasks they can hold. My longest project action note exceeds 1,400 lines, and the one for my Task Marker plugin is over 1,000 lines long. You can view its specific contents here:

Other Content: A project page also links to relevant entry notes, as well as other related notes and reference materials. This collection of content provides valuable context for project execution, ensuring that tasks are not carried out in isolation.

Clearly, project pages are comprehensive, and the very concept of a "project" in the PTKM framework is intrinsically tied to them.

2.1 The Value of Project Pages

Under the PTKM framework, a project page typically contains:

Project action notes

Entry notes for related topics

Permanent notes, project notes, and literature notes on related subjects

Other reference materials

In the Zettelkasten method, an "entry note" serves as a hub for notes on a similar topic. Since project pages also gather entry notes and other related materials, they function as a specialized type of entry note. When I need to find information on a specific topic, I can check either the relevant entry note or the project page.

Over the past five years, my system has grown to include over 240 projects and 159 entry notes. This data reveals that project pages have increasingly taken on the role of entry notes. While traditional entry notes are simpler and focus on aggregating notes on a topic, project pages are more robust, containing a wider range of elements tailored to a specific project or goal.

2.2 Locating Project Pages

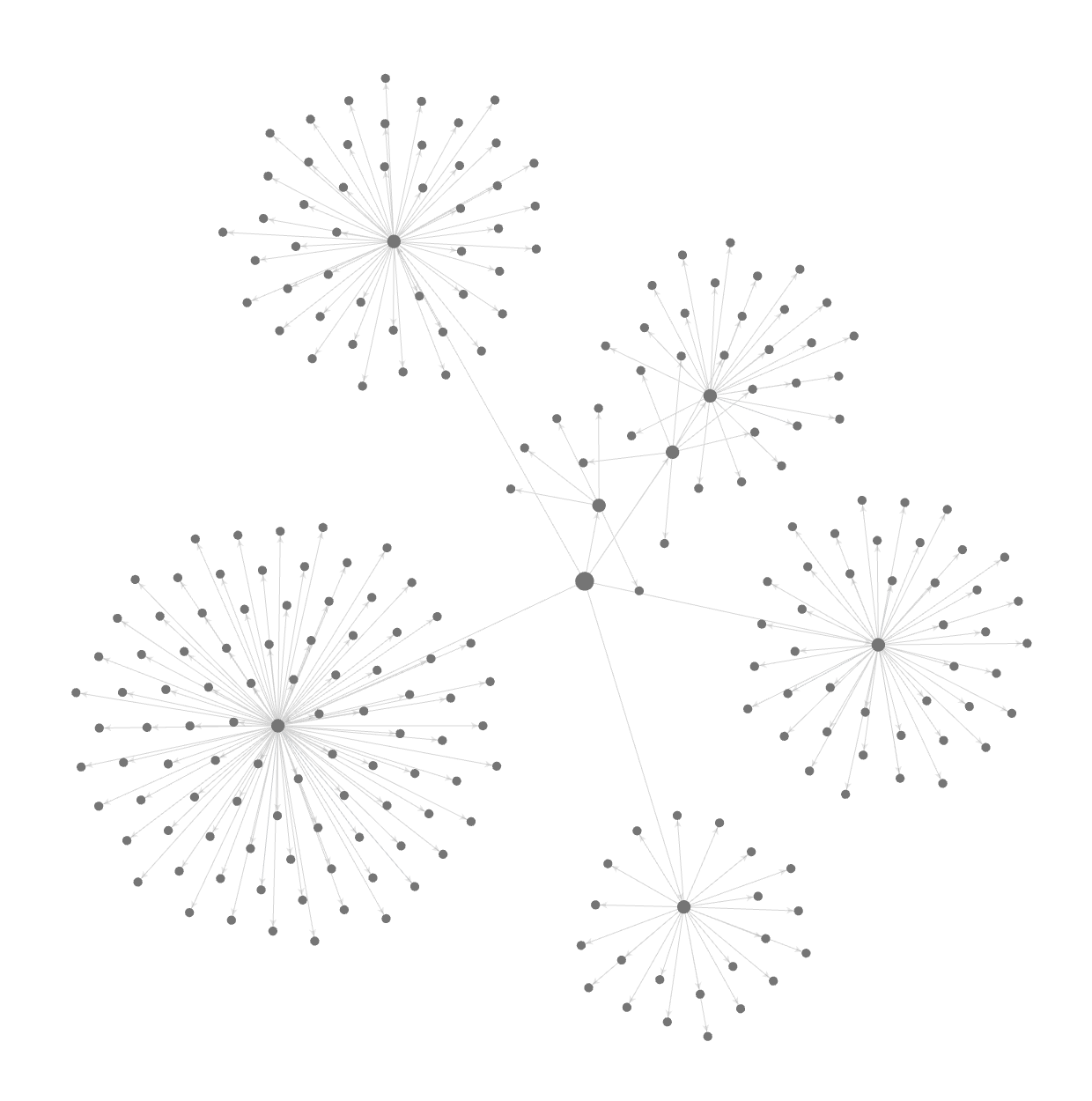

The image below shows all the project pages in my system, as seen in Obsidian's Graph View. I used ChatGPT's image analysis, which estimated 248 nodes, each representing a project page. While I haven't counted them manually, I used the Obsidian "Bases" and "Dataview" plugins to confirm that the number of project pages does exceed 240.

The Graph View reveals that my projects fall into five main categories, such as work and personal life. Beyond the Graph View, I have several other ways to track all my project pages:

Entry Notes: The large central node in the graph is an entry note that consolidates these five categories. Each category, in turn, links to its specific project pages.

Obsidian "Bases" or "Dataview" Plugin: Since my project pages are titled with the prefix "Project" and contain a corresponding tag, I can easily query all of them using plugins like "Bases" or "Dataview."

Folder Structure: Each of the five categories corresponds to a folder, which contains subfolders for storing the project pages. This allows me to navigate to them directly through the file system.

As you can see, I have multiple ways to access my project pages. This is an intentional application of the concept of redundancy, which I've discussed before. Redundancy enhances the system's reliability, ensuring I can always find my project pages. Even if I were to stop using Obsidian, I could still locate them using folder navigation and keyword searches.

3. A New Perspective on Long-term Project Management

The PTKM method defines and manages projects primarily from a long-term perspective. This approach stems from the inherent characteristics of projects in our work and personal lives. In essence, the nature of projects themselves dictates this long-term management perspective.

3.1 Project Complexity

Without careful consideration, we often underestimate just how complex projects can be. This complexity manifests in multiple dimensions.

3.1.1 INDIVIDUAL PROJECT COMPLEXITY

Consider travel and business trips—they're far more complex than they initially appear. How often have you forgotten to pack something important or failed to handle essential tasks before departure?

After numerous trips, I realized I needed a comprehensive checklist to manage all travel-related tasks. This ensures I don't forget pre-departure preparations, pack essential items, and handle both in-trip and post-trip matters. Since implementing this system, I rarely forget important items or tasks. Now, regardless of trip length, I can pack everything within 30-60 minutes and seldom overlook crucial details.

Even though a trip itself might last only a few days to two weeks, the preparation phase can extend much longer. Preparation often begins the moment I know I'll be traveling. This might involve preparing discussion materials and presentations, booking flights or trains, researching local transportation, attractions, dining options, and understanding local customs and precautions. As you can see, travel involves numerous complex elements that benefit from systematic, advance preparation.

To manage such projects effectively, I create dedicated project pages and treat them as full projects. A single travel project might span two weeks to a month or more from conception to completion, even though the actual trip is much shorter.

Of course, we don't create this complexity intentionally—it's simply an inherent characteristic of projects. While we might wish project management could be simpler, reality often dictates otherwise. We must adapt our management approach to match the nature of each project. Ultimately, what matters is making progress, not getting trapped by complexity itself.

Using travel as an example again: if we assume from the start that trips are extraordinarily troublesome and require exhaustive planning to prevent all possible issues, we might fall into a perfectionism trap. This can create anxiety and avoidance around travel. While advance preparation is valuable, we must remember that—like all projects in work and life—we cannot anticipate every detail. Unexpected situations will inevitably arise.

The key is accepting this reality. By not over-preparing, we can reduce travel-related anxiety. When surprises do occur, we won't be as shocked or panicked because we understand that unpredictability is a fundamental project characteristic. In fact, unexpected situations become far less daunting when we know how to approach and handle them.

3.1.2 COLLECTIVE PROJECT COMPLEXITY

If we followed traditional project management approaches—creating a separate project for every small matter—our systems would quickly become unmanageable. This mirrors what I've observed with note-taking: using atomic notes instead of longer, consolidated notes leads to an overwhelming number of individual items that become difficult to manage.

My current system contains over 240 projects. However, if I had followed traditional project management principles, this number could easily be 100 or even 1,000 times larger—potentially 24,000 to 240,000 projects or more. How would anyone manage that scale? How would you handle the tasks, relationships, and structures across tens of thousands of micro-projects?

3.2 Project Specificity

Many projects in our work and personal lives have a unique characteristic: they're ongoing and open-ended.

Consider personal growth, reading, watching movies, or exercise. These activities rarely have clear deadlines—they're continuous pursuits. In a broader sense, we might view them as goals, lifestyle choices, or life states rather than traditional projects.

We could certainly categorize system content into distinct types like projects, goals, and other categories. For instance, my project pages use a "Project" prefix in their titles, though I could easily use "Goal" or another prefix instead. I've discussed naming strategies in previous articles, emphasizing how consistent naming creates system redundancy, improving reliability and making future rediscovery easier.

However, treating everything as "projects" simplifies management. This is largely a semantic choice. What matters more is how efficiently we manage and advance these initiatives, not what we call them. You should choose whatever naming and management approach works best for you.

Personally, regardless of duration or whether something is technically a "project" or "goal," I've found no friction in managing them uniformly. When I think of any initiative, I can usually find the corresponding page quickly by searching for keywords in note titles. When my current keywords don't match what I used originally, I can find them through links, tags, folders, or other methods—techniques I've covered in previous articles.

What matters isn't precise categorization, but being able to conveniently find and advance these initiatives in daily work and life. Practical utility trumps formalism every time. This is why I treat everything as projects.

As you can see, the PTKM system takes a broad, inclusive approach to defining projects—which partly explains why my system contains over 240 of them.

3.3 Project Longevity

Most projects in the PTKM system have extended durations, largely due to the complexity and specificity characteristics we've discussed.

For simple tasks lasting just a few days, a checklist or basic note suffices—there's no need for full project management. Creating, managing, and executing projects all require time and energy.

When the overhead of managing a project exceeds the effort needed to complete its tasks, the project approach becomes inefficient. This is why I avoid creating projects for short-term, simple task collections—the management cost outweighs the benefit.

Conversely, longer-duration projects in the PTKM system offer significant advantages. By extending project lifespans, we avoid constantly creating and managing new projects, which would consume unnecessary time and energy. Long-term projects can deliver sustained value over time, as I'll explore further.

Remember: we manage tasks and projects because they serve our goals and help us achieve them. The purpose is never to manage for management's sake. We must avoid putting the cart before the horse.

3.3.1 LONG-TERM PROJECT EXAMPLES

Given these considerations, PTKM projects typically have extended durations—ranging from several months to a year, three years, five years, or even a lifetime. Here are several concrete examples of long-term projects.

Research Projects: Academic research projects commonly span years—one, two, five years, or longer. A complete research cycle might include grant applications, project management, literature reviews, research execution, algorithm development, experimental validation, paper writing and publication, and project completion.

Even a single research project contains numerous complex components. Each component might warrant its own project action notes, and some could be subdivided into sub-projects. For instance, presenting results at an academic conference involves result generation and analysis, paper writing, presentation preparation, and travel arrangements.

From a broader view, when one research project concludes, it often spawns follow-up research projects. In this sense, a single research project may never truly end, at least not in the short term.

Exercise Projects: Fitness projects can literally last a lifetime. For physical and mental health, we engage in various sports. I've personally played badminton for about ten years—it's helped me through many difficult periods.

Especially after reading "Outlive" in recent years, which emphasizes exercise's importance for healthy longevity, I'm even more motivated to maintain my fitness routine. It's not just the physical activity itself—the social aspects of sports are equally valuable for emotional health.

I've maintained badminton for a decade. Even if I eventually move away from badminton, I'll likely pursue other sports—I'm already exploring new activities and hobbies. From a project management perspective, this represents a lifelong project.

Consider this: whether badminton or other sports, they don't require daily attention but periodically involve specific activities—learning techniques, purchasing equipment, sharing experiences with others. Many projects in our work and personal lives share this characteristic. They don't need daily advancement, which is perfectly normal and realistic. After all, with 240 projects in my system, how could I possibly advance every single one every day?

Personal Growth Projects: Activities like self-development, software development, blog writing, and podcast creation can all be managed as projects—and most have extended timelines.

In software development, I released the first version of Task Marker in December 2022 and have continued developing it for two and a half years, though not with frequent updates. I initially created Task Marker to meet my own task management needs—specifically for changing task status and adding timestamps. Later, thinking it might help others, I open-sourced it.

Task Marker now has over 13,000 installations. While there's still a significant gap compared to top-ranked plugins, it gives me more satisfaction and sense of achievement than my academic citations! 😂

Since then, I've developed 11 additional plugins, totaling 12 so far, and I may develop more in the future. Each plugin can be viewed as an independent project without clear deadlines—new features need development, code requires maintenance, and so on.

This illustrates how software development contains multiple sub-projects and can be treated as a long-term project without a definitive endpoint.

In blog writing, I began publishing on multiple platforms about a year ago—for example, Medium and Substack. I plan to continue because there's still so much content I want to share.

Entering flow states while writing and finding that sense of peace are aspects I truly enjoy. Seeing people read and comment on my articles, plus receiving tips from strangers and friends, brings me happiness and satisfaction. These are likely important motivational sources that drive me to keep creating. There's a book called "Drive" that I haven't read yet, but it probably covers similar themes.

I'm uncertain how long this blog writing project will last—it has no clear deadline. It might continue for a long time, or it might evolve as my work and life focus and circumstances change.

4. The Value of Long-term Project Management

Adopting a long-term perspective for project management offers several significant advantages.

4.1 Reducing Management Complexity

As I've explained earlier, traditional project management approaches could easily inflate my system to 24,000-240,000 projects instead of my current 240. Such volume would make effective management virtually impossible.

The long-term project approach aligns with the "long notes vs. short notes" strategy I've discussed previously: it reduces management overhead through integration rather than fragmentation. Specifically, adopting a long-term perspective allows you to:

Consolidate related tasks and ideas within a single project framework

Avoid proliferating micro-projects

Minimize context-switching and maintenance costs between projects

The fundamental goal of this approach is to ensure project management serves people, not the other way around. By simplifying management complexity, we free up mental energy for what truly matters: execution and creation.

4.2 Leveraging Long-term Value

Long-term project management creates tremendous value through reusability. Consider travel planning: the first time you visit a destination, you invest significant effort in researching luggage essentials, flight options, hotel comparisons, and local attractions. By documenting these processes systematically—including specific steps, useful websites, pricing insights, and lessons learned—you create a reusable template.

For future similar trips, you can simply reference your previous project notes, avoiding duplicate research and dramatically improving planning efficiency.

Furthermore, long-term project management extends the value of projects beyond their completion dates. While a project like a vacation has a clear endpoint, its accumulated knowledge continues to provide value indefinitely. The notes, execution experiences, successful strategies, and even failure lessons become valuable assets for future endeavors.

In this way, a "completed" project transforms into a knowledge asset with enduring value. This value continuity represents the essence of long-term project management—projects may formally end, but their value persists.

4.3 Relaxed Status Management

A third major advantage of long-term project management is the ability to adopt a more relaxed approach to status tracking. You don't need to meticulously maintain the precise status of every project—whether it's in the seed stage, in progress, or completed. Projects can naturally remain in their current state as long as this doesn't disrupt your workflow.

For instance, when a project reaches completion, you can leave it as is without performing tedious administrative tasks: moving files to archive folders, marking every task as completed, or reorganizing related notes. These seemingly "proper" procedures often consume considerable time and energy while providing minimal value.

This relaxed approach doesn't mean neglecting valuable content. Instead, it emphasizes selective organization over comprehensive management:

Immediate value tagging: When you discover important information, immediately add relevant tags or create quick links

Priority status marking: Apply special status indicators only to truly important content

Strategic linking: Connect valuable discoveries to related projects or notes as needed

4.4 Highlighting Key Projects

The fourth significant advantage of long-term project management is the ability to maintain hundreds of projects without experiencing management anxiety. Even with 240+ projects in various states, effective management remains possible. The key is developing clear priority awareness—always knowing what truly matters in your current phase of life.

For instance, at any given time, you might be juggling two work projects, a fitness regimen, and learning a new skill. By clearly identifying these core priorities, you can direct your limited time and energy to what matters most.

As for the other 200+ projects, you can employ what I call "strategic neglect." This isn't avoidance but rather efficient resource allocation. When your priorities are clear, you naturally focus your energy on core projects while allowing others to remain dormant until needed.

This approach proves far more effective than attempting to actively manage every project simultaneously. Focusing on priorities always yields better results than dispersing energy across trivial matters. This management philosophy embodies the 80/20 principle:

Invest 80% of your time and energy in truly important core projects

Allocate the remaining 20% to secondary projects

As you gain experience with this approach, you might find yourself asking an even more powerful question: "For truly unimportant matters, why allocate any time or energy at all?"

5. Project Development and Evolution

5.1 Dynamic Changes in Projects

While the PTKM system emphasizes long-term projects, their creation and development remain inherently unpredictable. Even established long-term projects can evolve and branch into smaller, more specific projects as needs change. For instance, within the broader "Life" category, I might create a "Life Exercise" project—a distinct entity that nonetheless remains connected to the larger life domain.

Consider a "Life Shopping" project as another example. When contemplating a significant purchase that requires substantial funds, the process might involve extensive research, financial planning, and comparison shopping over an extended period. While we couldn't have anticipated this specific need in advance or predicted whether we'd ultimately make the purchase, we can adapt by creating appropriate sub-projects or dedicated project action notes when the need arises.

This flexibility is key—when creating projects, we start with rough outlines based on current needs and ideas, using provisional names and general positioning. As circumstances evolve, we can refine the project name, create sub-projects, or restructure the hierarchy entirely.

At its core, project creation and evolution reflect the changing demands of our work and life. From a broader perspective, how our projects evolve mirrors the development of our entire organizational system and, ultimately, our personal growth journey.

5.2 Project Status

Project status tracking provides a powerful framework for managing multiple initiatives simultaneously. By categorizing projects according to their current state, we can focus our attention on specific projects at specific stages, preventing the overwhelm that might otherwise come from trying to actively manage hundreds of projects at once.

In the PTKM system, projects typically move through the following states:

5.2.1 SEED

The "seed state" represents the earliest stage of project development—when an idea first emerges but remains largely undefined. For example, we might have the thought, "I'd like to visit Japan someday." At this nascent stage, all key elements remain undetermined: when we might go, which cities we'd visit, where we'd stay, how we'd travel between locations, who might accompany us—none of these questions have answers yet.

I call this the "seed state" because, like a seed containing the genetic blueprint of a future plant, these early project ideas hold infinite possibilities but haven't yet broken through the soil into tangible form. At this point, the project exists primarily as potential—a concept waiting to be activated and refined through further thought and research.

5.2.2 READY TO START

As an initial idea develops, we gradually accumulate related thoughts and notes. For the Japan trip example, we might create a dedicated folder to collect articles about Japanese culture, or recommendations from friends who've visited. Over time, as these notes grow to five, ten, or more items, the idea becomes sufficiently developed to warrant more substantial action.

This progression marks the transition from "seed" to "ready to start"—the project shifts from a vague possibility to a relatively concrete plan deserving focused attention. At this stage, we begin more specific research: comparing hotels in different neighborhoods, investigating flight options and pricing patterns, determining which seasons offer the best balance of good weather, reasonable prices, and manageable crowds.

We might also discuss our emerging plans with friends, generating new ideas and insights through these conversations. These fresh perspectives connect with our existing research, making the entire project concept more robust and feasible. The project now sits comfortably in this "ready to start" state, awaiting the right moment for official launch.

5.2.3 IN PROGRESS

When the project enters the "in progress" state, planning transforms into concrete action. For the Japan trip, this would mean booking flights and accommodations, creating detailed daily itineraries, and assembling necessary travel items. The project shifts decisively from theoretical planning to practical implementation, with decisions becoming increasingly specific and time-sensitive.

During this execution phase, the project naturally generates additional tasks and considerations. We might need to purchase travel adapters, reserve seats on the Shinkansen between cities, research operating hours for key attractions, or map out efficient daily routes. Some of these tasks were anticipated from the beginning, while others emerge only after deeper research into our destination.

This organic proliferation of tasks characterizes the "in progress" state—the project is no longer a static plan but a dynamic system that continuously evolves and refines itself as implementation proceeds.

5.2.4 PAUSED

After returning from Japan, we'd naturally transition back to daily routines and other priorities, placing the travel project in a "paused" state.

At this juncture, the flexibility of the PTKM system becomes apparent. If we anticipate similar future trips, we might restructure the project in one of two ways: either designate the Japan trip as a sub-project within a broader "International Travel" parent project, or maintain it as a standalone project while creating parallel projects for future destinations. The beauty of this system is that either approach works—We can always restructure later as our needs evolve.

Projects enter the paused state for various reasons, each with different implications:

Natural completion: As with the Japan trip example, the goal has been achieved, and we're simply moving on to other priorities

External dependencies: Progress depends on feedback from others or conditions beyond our control

Deliberate abandonment: We've actively decided to stop the project due to changing priorities or diminished interest

Strategic postponement: The project was planned for a specific time but needs deferral due to more pressing matters

This diversity of pause scenarios demonstrates the nuanced reality of project management in practice.

5.2.5 END AND ARCHIVE

Eventually, a project may reach its "end" and "archive" stage. At this point, we can formally mark it as completed and relocate related files to archive folders. Even a seemingly straightforward travel project will have progressed through the complete lifecycle: seed → ready to start → in progress → paused → end → archive.

Importantly, the act of archiving a project is itself a task—and typically not a high-priority one. When compared with other pressing matters in our system, formal archiving can often be deferred. If our task list contains more critical items requiring attention, we can and should prioritize those over administrative archiving tasks.

The psychological sense of project completion often carries more significance than the mechanical act of archiving in the system. When we've internalized that a project has concluded and no longer requires our attention or energy, this mental closure may be more meaningful than the formal archiving process. After all, if we've already established internally that we won't be investing further resources in this project for the foreseeable future, hasn't the project effectively reached completion in the ways that truly matter?

5.3 Evolution of Project Status

As emphasized throughout this article, long-term project management forms the cornerstone of the PTKM system. Consequently, most projects follow a typical status trajectory of: seed → ready to start → in progress → paused, with relatively few reaching the formal "end" and "archive" stages. This pattern aligns perfectly with the fundamental nature of long-term projects and represents an intentional outcome of the system's design.

Meanwhile, shorter-cycle projects may skip certain status transitions entirely, which is equally valid. The comprehensive progression through all status stages isn't what matters—what's crucial is mastering the art of focused attention: during any given period, you need only concentrate on a select few important projects in their current states.

This "selective attention" approach is precisely what enables effective management of numerous projects simultaneously. Rather than anxiously monitoring every status change across hundreds of projects, you simply identify the core projects deserving attention in the current phase and direct your energy accordingly.

6. Managing Project Progress

As I've mentioned, the PTKM framework is designed for long-term project management. With over 240 projects accumulated in my system over five years, all running in parallel to varying degrees, a natural question arises: how does one effectively manage such a large portfolio?

Project progress management can be approached from two complementary dimensions: managing individual projects and managing the entire project ecosystem.

6.1 Individual Projects

In previous articles, I've detailed how to use Gantt charts for long-term project management, including methods for timeline planning and progress visualization. These techniques provide powerful frameworks for tracking individual project development. Readers interested in these specific approaches can explore those resources for in-depth guidance.

6.2 All Projects

For managing the complete project portfolio, several powerful tools prove invaluable:

Dataview queries: Enable filtering projects through flexible query syntax

Obsidian Bases: Provide intuitive project query and visualization functions

These tools support sophisticated multi-dimensional filtering, allowing you to:

Filter by project status (seed, ready to start, in progress, paused, etc.)

Filter by project category (work, life, development, etc.)

Filter by priority level or time range

However, even with these powerful query and filtering capabilities, managing hundreds of projects simultaneously presents significant challenges. While our focus strategies help by directing attention to a select few core projects during specific periods, the sheer scale of managing 240+ projects and more than 100,000 tasks inevitably creates complexity.

In separate articles, I'll explore advanced strategies for parallel project management and techniques for handling large task volumes to address these complexity challenges more comprehensively.

7. Conclusions: Redefining the Boundaries of Project Management

The PTKM method offers a fresh perspective on project management. By adopting a long-term view, organizing work into project action notes or sub-projects as needed, and allowing projects to flow naturally through different states, this approach transforms how we think about managing our work and life initiatives.

The five core advantages of this long-term perspective are:

Strategic Entry Points: Project pages serve as specialized entry notes, dramatically improving information retrieval and access

Reduced Complexity: By consolidating related activities into long-term projects, we significantly reduce the total number of projects requiring active management

Enduring Value: Completed projects provide valuable references and templates for future initiatives, creating a compounding return on investment

Flexible Management: The relaxed approach to status tracking reduces administrative overhead and maintenance costs

Priority Focus: By highlighting truly important projects rather than attempting to actively manage everything, we direct our limited energy where it matters most

When we expand our concept of project management to encompass more aspects of work and life through this long-term lens, we discover that PTKM isn't merely a management methodology—it's a philosophy for living. This approach helps us maintain clarity and direction amid the complexity of modern life, allowing us to identify and focus on what truly matters within the overwhelming flow of information and demands on our attention.

Related Reading

How to Manage Long-Term Projects in Obsidian: My Proven Approach

In task management, tools like Todoist, Obsidian Dataview, and Tasks help us manage specific tasks. However, when it comes to overseeing the overall progress of a project, traditional task management tools often fall short. This article will introduce how to use Mermaid Gantt charts effectively in Obsidian to manage long-term projects (for example, last…

The Hidden Journey: How Tasks Mirror Your Life's Lessons

On that afternoon when sunlight streamed through the bus window onto my body, with familiar melodies playing in my earphones, I suddenly thought of a question: We handle various tasks every day, but have we ever wondered what kind of journey a task goes through from birth to completion?

The Strategy of Task Management: Starting Early, Redundancy, and Reliability

Recently, I shared how to implement redundancy in note systems through folders, tags, links, note naming, timestamps, and other methods to improve system reliability and discover unexpected connections. In fact, the theme of this article—starting tasks early—is essentially

From Chaos to Clarity: My Multi-Vault Approach to Obsidian Knowledge Management

A comprehensive guide to organizing multiple types of Obsidian vaults for improved performance and workflow

Long Notes or Short Notes: My 5-Year Reflections

In today's flourishing digital note-taking tools, we have unprecedented freedom to record and organize our thoughts. However, this freedom also brings confusion in choices—should we follow the traditional Zettelkasten (slip-box) method using concise atomic notes, or can we confidently record lengthy content? This question has troubled many note-taking e…

How I Used AI to Develop 10 Obsidian Plugins

Over the past two years, I have harnessed the power of AI tools to develop 10 Obsidian plugins—a journey filled with frustration, learning, and ultimate satisfaction. Despite having little knowledge of TypeScript at the start, AI transformed the way I approach coding, enabling me to create solutions that address long-standing gaps in my workflow. This j…

https://ptkm.net/obsidian-plugins

The Strategy of Note Taking: Folders, Tags, Links, and Redundancy

Managing a growing note library—especially when approaching or have surpassed 10,000 notes—can feel overwhelming. Yet the goal is clear: spend minimal time and effort on organization while maximizing efficiency when retrieving important ideas. The system itself should serve your projects, tasks, and life goals, not become an end in itself.

The Strategy of Note-Taking: Eight Types of Idea Connections

In a previous article, I introduced how to build a redundant note system through folders, tags, links, note naming, timestamps, and other methods to improve the reliability and flexibility of the system, which helps discover unexpected connections. The ability to discover unexpected connections is one of the characteristics of the Zettelkasten method.

This is very thorough. You deserve more subs. I hit subscribe.